In 17th century Salem, Massachusetts, mass hysteria spread as rumors of witchcraft filled the town. Once accused, you were considered guilty until proven innocent, with the only way of escaping execution being to plead guilty. Feigning innocence would result in death. Today, AI usage has brought a modern twist to the Salem Witch Trials – but instead of accusations of witchcraft, it has now become accusations of using AI in writing.

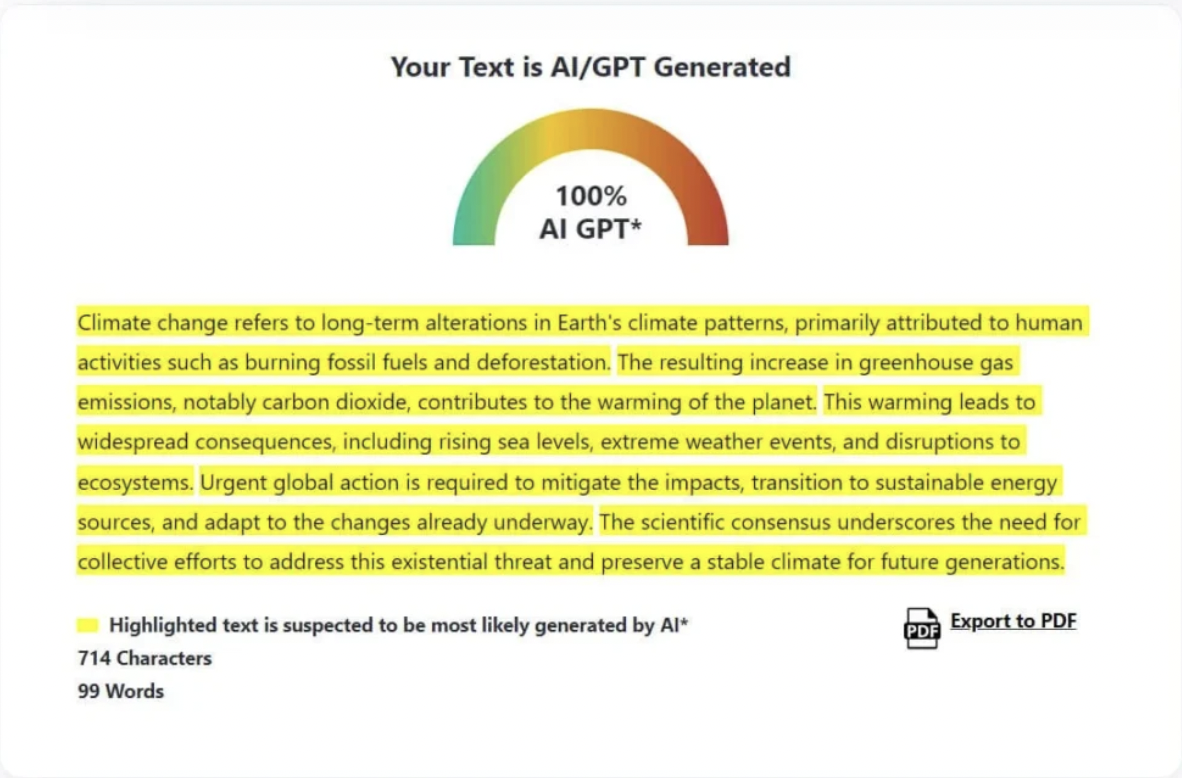

I’m sure most of us have felt this dreadful feeling before. Imagine you’ve just finished writing an essay for class, and just as a precaution (or partially out of subconscious fear) you decide to put it into ZeroGPT (a free AI detector that identifies text generated by AI), expecting it to spit back 2 magical words: “0% AI!”. But instead, an ambiguous percentage flashes across the screen, various sentences are highlighted bright yellow, and a tiny message appears on the bottom: Highly suspected of being AI-written. How could the work that I’ve written myself be considered AI? But more importantly, how can I defend my own work as not being AI? Thankfully, this is a hypothetical for most of us, but for some, this dilemma is a reality.

Due to the rise in generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT, today’s universities face a unique challenge: students wrongfully using generative AI. The response? AI detectors. However, these detectors are not 100% accurate, and are known to be littered with false positives. Across the United States, student expulsions due to generative AI have risen, raising the stakes for students. In late 2024, University of Minnesota Ph.D. student Haishan Yang was expelled after allegedly using generative AI on an exam. Haishan denies the accusation in a federal lawsuit. Unlike the Salem Witch Trials, one is not condemned to death, but one accusation of academic misconduct still has devastating effects on the student. For some it is a warning, while for others it is expulsion. To understand how we can combat this problem, we must first understand how these detectors work.

AI detectors like ZeroGPT operate through algorithms that analyze patterns of AI generation. Similar to how Generative AI works, AI detectors are trained on datasets of AI and human-generated content. By utilizing machine learning and natural language processing (NLP), these models are able to recognize the differences between human and AI outputs. This includes evaluating sentence structure, word choice, repetitive phrasing, and overly formal language. Sounds pretty secure, right? Unfortunately, AI detectors have led to an overwhelming number of false positives and a low detection rate.

These models traditionally advertise a 99% success rate, but the 1% of failure opens the floodgates for a plethora of false positives and incorrect classifications, revealing that the success rate is seemingly less than it appears. A 2023 paper from Stanford found that detectors are particularly unreliable for non-native English speakers. The study noted that the detectors were “near-perfect” when evaluating U.S.-born eighth-graders, but classified 61.22% of non-native English students as AI-generated. So what does the percentage of human-writing-or-AI-writing actually mean? Stanford professor, James Zou explains this best: “They…score based on a metric known as ‘perplexity’. Perplexity relates to the refinement and sophistication of the writing, something that naturally leads to non-native speakers falling behind. So how can we combat this?

Much like those accused of witchcraft during the Salem Witch Trials, there isn’t much someone can do when accused of using AI. Some possible solutions include gathering previous written works to make comparisons or having your research history available. The best way to avoid being accused is doing all your work on one document, so an edit history exists. This could mean doing your work on a platform like Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Lastly, we should all collectively have less faith in fallible systems like AI detectors. AI is built and trained on the data that we feed into it, and too much of the time, the data doesn’t tell the whole story. During the Salem Witch Trials, those accused were not heard out. Today, we must not repeat the past and have more clemency for those accused of using AI.