The Illusion of Meritocratic Achievement

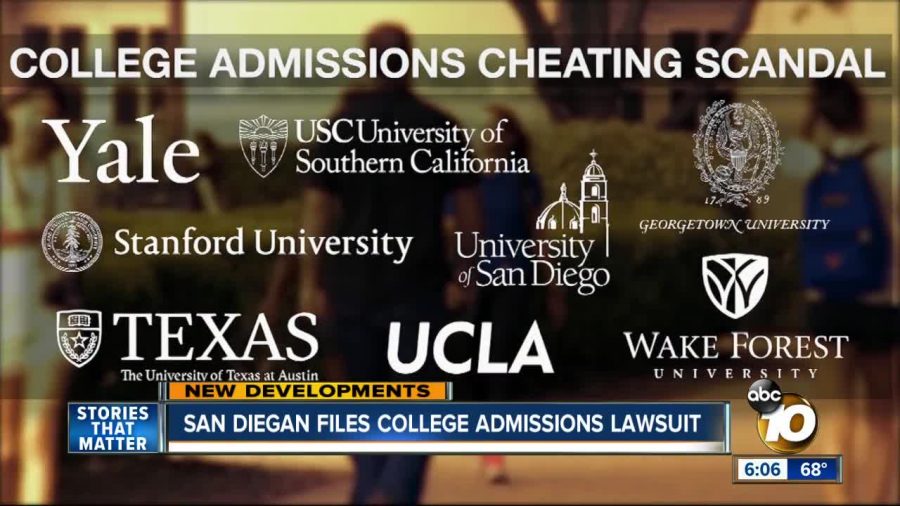

Photo courtesy KGTV.com

Over the last couple of weeks Americans from Westwood to New Haven have been forced to reckon with cheating and corruption at the very heart of our most cherished meritocratic institutions. The Justice Department’s slew of indictments and charges against numerous individuals involved in a massive college admissions fraud has revealed an underworld of graft and bribery that frankly almost everyone expected. As we cope with the fallout from the college admissions scandal, the scandal should hopefully be a mechanism for deep reflection about the fundamental rot at the heart of American society–and perhaps offer some important solutions.

Elite colleges have increasingly become a microcosm of the rifts in American life, places where inborn privilege is solidified and differences of class give way to the illusion of meritocratic achievement. Why shouldn’t wealthy individuals attempt to game the system with the imperious assumption that everything is for sale? That being said, the very trick of this fraud–and the reason it is so captivating–is that it mixes in equal measure breathtaking lawlessness and pristine ignorance. Many commentators have rightly asked why anyone should purchase SAT massaging and fake sports resumes when the individuals involved could just as easily donate a building or find some other way of making their child a “development” candidate. Why walk through the front door loudly with a proverbial pile of cash when the side door was open the entire time? Eventually it will fall to ordinary Americans to reckon with the underlying realities of the process and the assumptions that drive such blatant criminal behaviour.

The main responsibility for this sordid state of affairs lies at the feet of a college-industrial complex that places emphasis on arbitrary, byzantine procedures and a unique vision of shallow excellence. Elite schools could fill their halls many times over with the ranks of valedictorians, perfect SAT scorers, and AP scholars The ways that they differentiate lead to ugly debates about affirmative action, legacy admissions, donations, and athletes. The nature of these debates does not bear in-depth analysis within this column; however, the cumulative effect is a slavish devotion to ingrained prejudice, institutional prerogatives, and closed-mindedness about what constitutes an “ideal” applicant and what by extension is worthy of admittance. That mindset is not to suggest that prestigious schools are the “only” option; it is merely to say that our unhealthy obsession with flawed and arbitrary definitions of merit is producing a new aristocracy that will end up passing on increasing amounts of generational inherited wealth. This columnist can think of nothing more contrary to the American Dream in both a social and economic sense.

There is also a certain unavoidable irony in writing this column from precisely the sort of pre-college preparatory bastion that emblematizes America’s fascination with meritocratic upward mobility. There is arguably little doubt that much of what makes Flintridge Prep both a great high school and a good investment is the rigorous environment that prepares well-rounded and adequately socialized college applicants. But the events of the last several weeks should serve to put matters into perspective: the eventual pursuit of higher education, while worthy, should not be allowed to skew one’s goals, one’s work-life balance, or one’s mental wellbeing. There are not any easy fixes to the problems at hand. To change the college admissions process and its endless ancillary functions would require a level of political and social will that is simply hard to come by. Thus, teenagers will still find themselves tasked with maintaining their place in an endless line while being forced to wonder almost furtively if others got a fast pass.