“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands…may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.” These words, written by James Madison leading up to the ratification of the Constitution, are precisely why Congress exists: to provide a check on the power of the executive and prevent the American president from becoming a king by another title. However, the centuries since have exposed a multitude of complicating issues: polarization in the legislative branch, the increasing prevalence of executive orders and emergency declarations, and Supreme Court rulings that expanded executive power. Now, Congress in the modern age is becoming a dangerously weak entity.

One of the primary reasons Congress is losing its influence is its own dysfunction. In the 93rd Congress, which was inaugurated 50 years ago, 772 bills were enacted into law. Totals similar to this were commonplace through 1992. After that, however, lower totals increased so much in prevalence that only one Congress has cracked 600 enacted laws since the turn of the century. The 118th Congress, which ended in January 2025, was the least productive in decades, enacting only 274 laws. Much of this ineffectiveness stems from increased political polarization: in the House of Representatives at the end of 2022, Democrats had grown 22.58% more liberal on average since the 92nd Congress (inaugurated in 1971), while Republicans had grown 104% more conservative. At the same time, ideological diversity within each party had sharply curtailed, with only about two dozen “moderate” members of the House remaining compared to over 160 in the 92nd Congress. However, growing hyperpartisan attitudes don’t tell the whole story of Congress’ decline. After all, the only way for an institution to lose its power is for other institutions to take it.

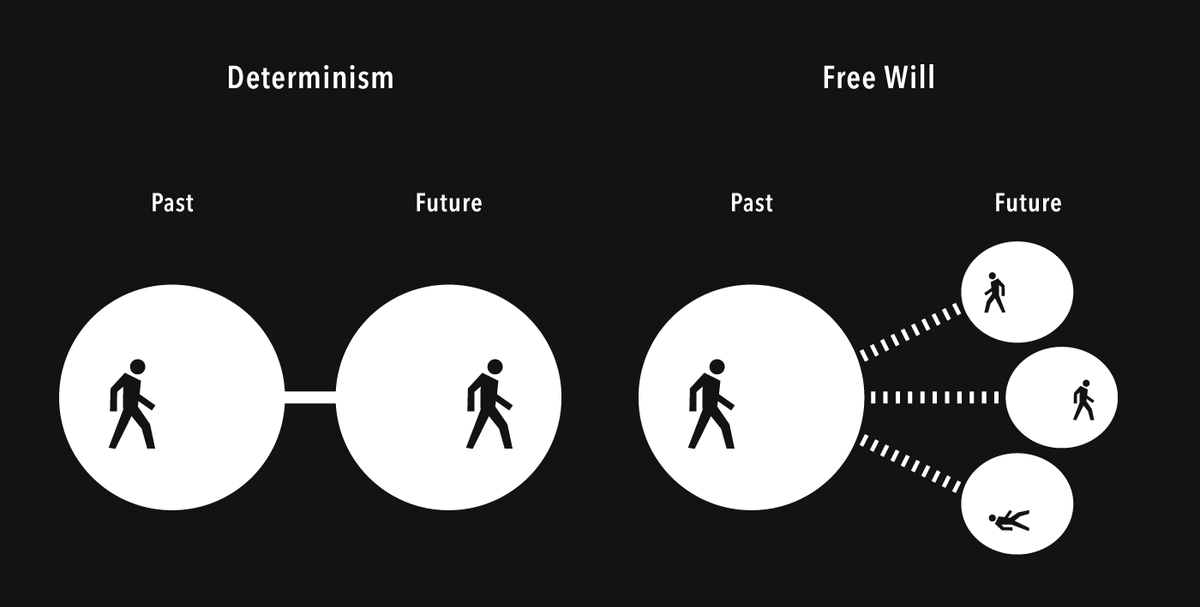

The executive branch is one of those institutions. The tendency for presidents to fulfill their policy objectives through executive action has put the executive branch on the path of absorbing the legislative functions of Congress. While the actual amount of executive orders has decreased in the last 50 years–no president has signed more than 300 in a single term since Jimmy Carter, whereas signing close to 1000 was business as usual in the early 1900s–the centrality of those orders to presidential policy has vastly increased. In the presidencies of Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden, nearly half of the total amount of executive orders were signed within the first 100 days of the term. This suggests that they were policies connected to each president’s top priorities. In recent presidential terms, executive orders have attempted to tackle sprawling issues in ways previously reserved only for laws – including the Biden administration’s pricey student loan forgiveness programs; the Trump administration’s wide-ranging directive to curtail DEI in hiring and education; and the Obama administration’s landmark Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration program. Recent presidents have also shown more openness to using their powers under the National Emergencies Act to achieve policy goals, some of which have been legally dubious. A prominent example of emergency power usage is the Trump administration’s declarations on trade imbalance and the flow of drugs, which claim unilateral authority to impose tariffs on a multitude of countries. However, even if Congress has gotten less efficient and the executive branch has filled the gap, the final branch of government–the judiciary–still theoretically acts as a final bulwark against the presidency.

The gradual decline of that principle is what puts “the nail in the coffin,” so to speak, of our dire situation. Various court rulings have chipped away at limitations on the executive branch for decades. In United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936), the Supreme Court ruled that “Congress itself is powerless to invade” executive decisions on foreign affairs, establishing a precedent for presidents to make their own call on national security issues. This precedent is what has informed a series of high profile decisions regarding the balance between national security and the need to involve Congress, including the Holtzman v. Schlesinger (1973) ruling that declined to overturn the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which granted President Lyndon B. Johnson broad power to conduct the Vietnam War. More recently, this idea of deference to the executive on issues of national security has spilled over into disputes about the application of emergency powers: the current Supreme Court has often either sided with Trump’s broad interpretation of his own powers or allowed such controversial executive actions to stay in effect for months as their legality is challenged. An unwillingness to challenge the judgment of the executive branch has led the judiciary to enable Congress’ loss of power.

Congress still has time to aggressively reassert its rightful authority, but for now, a perfect storm of its own dysfunction and the courts allowing the executive branch to push its power to the limit has made it an increasingly irrelevant body.