The Metaverse: Will Facebook’s Newest “Social Technology” Live up to its Utopian Ideals?

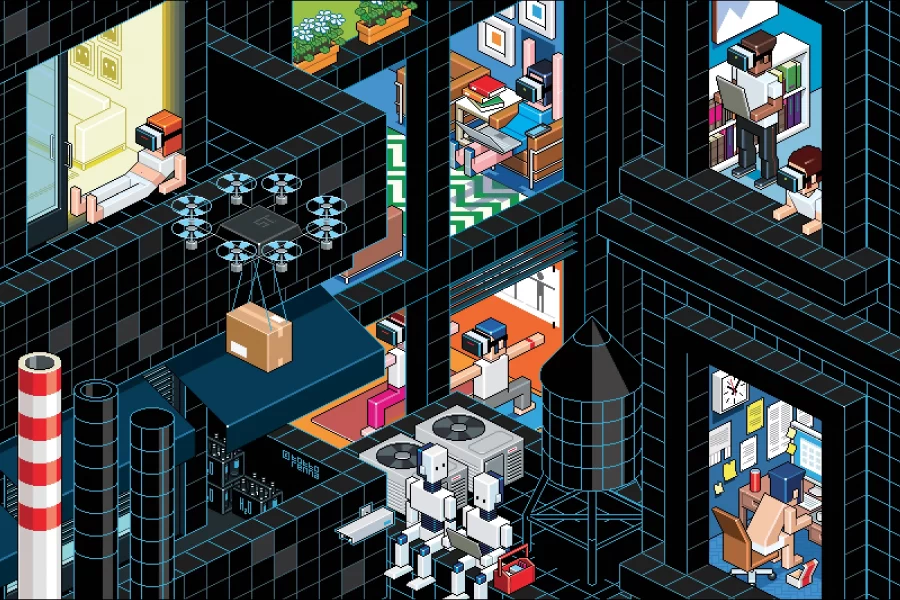

Photo courtesy Time

On October 28, Facebook announced its plans to change its corporate name to Meta. A reference to the metaverse, a term first coined in science fiction, Meta plans to create an all encompassing virtual world. This was outlined in their keynote, in which founder and CEO Mark Zuckerburg presented the public with renderings of virtual spaces for business, recreation, and education all united with one platform. To accomplish this, Meta will spend 10 billion dollars and hire 10,000 workers to bolster the virtual and augmented reality parts of their “Social Technology” wings.

This decision comes at a time when Facebook is increasingly coming under bipartian fire from lawmakers and the public over its very likely role in spreading misinformation and hate speech, specifically around vaccines and the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the 2020 election and politics. A move towards some kind of metaverse, even if unsuccessful, can help to move public attention away from the social media platform that is viewed by many as contributing to a decrease in mental health among teenagers and the growing presence of extremism online. By moving towards a new platform, Meta also attempts to reclaim power over its app which had usually been at the behest of whatever operating system it is on (namely IOS).

Meta is not the only tech giant to change its name, in 2001 Google rebranded to Alphabet in order to separate its profitable search engine from other branches of the company. Other companies have changed their corporate names for a variety of reasons, ranging from PR stunts to responses to public criticism. In 2003, Philips Morris, a company whose holdings include cigarette manufacturer Marlborough and various cigar makers, changed the name of its North American subsidiary to Atria. Even without making actual change within the company, changes like these attempt to separate a company from its troubled past and form a new “forward thinking” corporate identity.

In many ways the public response to Meta’s name change is just what Meta looked for- headlines have been awash with responses ranging from warning about the social implications of these new virtual spaces to listing which stocks will best respond to its technical needs. Companies too have taken notice of Meta’s recent shift and have begun to retool their brands in order to capitalize on the metaverse. Patents filed by Nike show that it may be preparing virtual branded items in some kind of metaverse. In addition to apparel brands, studios like Disney seem to have taken an interest in this new form of media as well. The Hollywood Reporter writes that during an earnings call CEO Bob Chapek outlined Disney’s plans to integrate their content into the metaverse.

With what seems to be a significant response from other corporations, it’s hard to see Meta’s change as purely window dressing or a simple diversion. However, if we are to see the “metaverse” become an increasing part of our daily lives, some important questions must be answered first. We must ask ourselves whether we are comfortable with companies like Facebook having an ever greater role in shaping our social, commercial, and recreational interactions both on and offline. The early utopian dreams of social technology, promised by the companies that have created Facebook and other social networks, have been sullied by the commodification of online spaces and their predatory behavior. Virtual and augmented reality would allow for corporations to blend advertisements and corporate oversight into even the most intimate parts of our daily lives. The metaverse can be a near utopian expression of our human desires for connection and play (as Meta has portrayed it), or it can amplify the darkest patterns of our current social media, exploiting these very desires for profit. Time can only tell which is realized.

Grade: 12

Years on Staff: 3

Why are you writing for the Flintridge Press?

The Press has been a great way for me to share my writing on politics...