The People of Hong Kong Should Continue to Protest

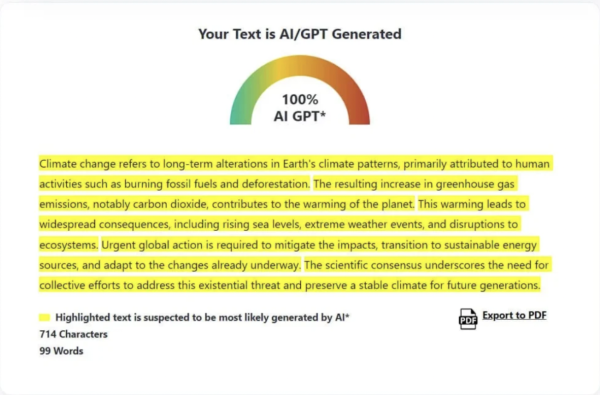

Photo courtesy Politico

Residents gather at a shopping mall in Sha Tin to protest a teenage demonstrator shot at close range in the chest by a police officer.

Change is brewing in Hong Kong, whether China likes it or not. Since June, millions of Hong Kong citizens have taken to the streets to challenge recent laws as well as China’s control over the territory. What began as an uprising against an extradition law has turned into a quest for increased democracy. The protests have gained the world’s attention, putting China in a crucial position. With a trade war underway and a global reputation at stake, China faces an enormous political dilemma and cannot afford to crack down on the protests with large-scale force. The people of Hong Kong have encountered a rare opportunity to test China and potentially gain democratic reform which they must take advantage of by continuing their protests.

When Hong Kong was handed over to China by the British in 1997, the National People’s Congress gave the territory fifty years of semi-autonomy. However, most of Hong Kong’s political power belongs to China, and only a fraction of Hong Kong’s population has voting rights. Most Hongkongers are unhappy with current leader Carrie Lam and the voting system that elected her. The system, far from being truly representative, attributes its power to Chinese representatives who are backed by Beijing. Hence the Chinese Communist Party plays a decisive role in who becomes the Chief Executive. Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s citizens lack the freedom to elect whoever they support, which is why universal suffrage is arguably the protesters’ most pressing demand.

China is not in a position to forcefully punish the Hong Kong protesters. The Chinese government is emerging as the world’s dominant power and cannot afford a blow to its reputation. Sending the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) into Hong Kong would jeopardize relations with the West and with its allies, likely causing repercussions such as a rupture in trade deal negotiations or an increase in skepticism surrounding Chinese foreign affairs. Xi Jinping (China’s president) is currently in the process of gaining allies, as many countries are still wary of trusting China. Furthermore, the potential backlash against an incident in Hong Kong is too risky, given China’s political situation. Even Lam is aware of this, stating in August that China “Has absolutely no plan to send in the PLA… Because they know that the price would be too huge to pay.” (Reuters)

Hong Kong is also an asset to China’s economy. Hong Kong serves as one of China’s links to the West, and Hong Kong companies are littered with Chinese investment. The ongoing protests have damaged Hong Kong’s economy, causing investments to weaken. Since mid-June, when the demonstrations first gained significant momentum, the Hang Seng Index (HSI) has dropped more than 100 points or around 5%. Thus, China suffers as the protests continue. If China wants to recover its assets, it must find a way to end the protests before they cause more losses. However, approaching the demonstrators with violence would be a blow to both economies and likely cause the HSI to drop even more.

A violent crackdown is unlikely, even given China’s history with public dissent. China has proven to be unafraid to use force, which it did in Tiananmen Square in 1989 against a mass of students and their pro-democracy movement. But that was thirty years ago when China was more communist and lacked a global influence. China was also somewhat able to cover up its tracks, which would be impossible today with the media and technology. Hence a repeat of the Tiananmen Square Massacre would be improbable due to all its potential consequences.

With the protests showing no signs of stopping, China must attempt to bring them to an end, or it will continue to suffer. Equipping the police with shields and teargas has proven especially ineffective. China may resort to banning the protests’ organizational platforms: social media and messaging sites. This option, though practical, would not succeed. It is far too late to outlaw modes of communication; the cat is already out of the bag. The protesters would find a way to dodge the punch and continue to assemble. It would be nearly impossible to drop a firewall into Hong Kong, whose citizens proudly embrace social media and communication. There are also too many possible loopholes such as VPNs that would tremendously weaken the power of a firewall.

Giving in therefore may be one of the only decent and realistic options. Because China knows that it will eventually assume full control of Hong Kong in 2047, it would likely be more lenient toward the people’s appeals. Authorities have yet to show any signs that would suggest listening to democratic demands, but Lam’s government has promised to erase the original extradition law. As the protests drag on, China will become more desperate to bring them to an end, hence also more likely to back down or to make a compromise.