August’s Democratic National Convention (DNC) has firmly cemented the party’s shift toward

Kamala Harris as its future leader. This swift change in direction has sparked intense debate within political circles over what it signifies for the party and the democratic process itself.

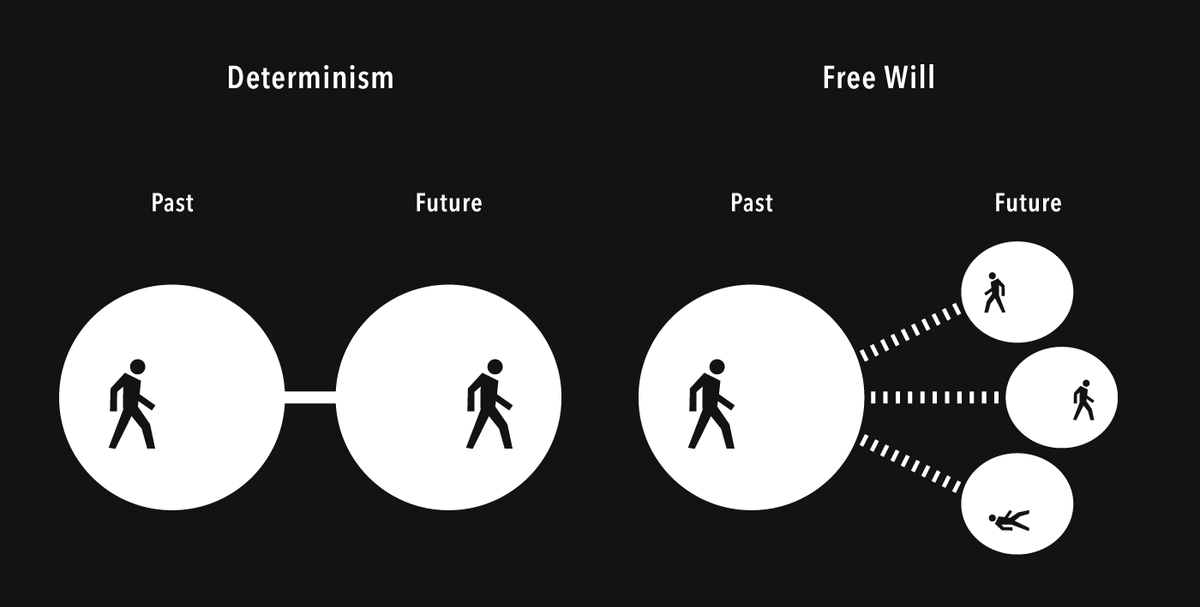

Proponents argue that the pivot highlights a thriving democratic institution willing to recognize its shortcomings, course-correct, and prioritize the broader interests of Americans over those of an individual leader. On the other side of the coin, critics highlight that Harris was chosen without a primary, declaring that clandestine schemes spearheaded by party elites undermine our democratic systems. Is this democracy at its finest or reason to sound the alarms?

But first, are both views even mutually exclusive? The ideas of 19th century philosopher and political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville say no. In his classic work “Democracy in America,” Tocqueville praises but also raises grave concerns regarding the democratic deliberation process. The most famous critique: the “tyranny of the majority.”

Tocqueville feared the power of the thoughts and opinions of the masses—a power that could effectively be used to silence opposing opinions out of a form of peer-pressure. In “Democracy in America,” he writes:

As long as the majority is still undecided discussion is carried on; but as soon as its decision is irrevocably pronounced, a submissive silence is observed, and the friends, as well as the opponents, of the measure unite in assenting to its propriety

Antithetical to democracy, pressures to conform to the majority silence individual thought. Jason Willick of the Washington Post adopts this analysis, seeing parallels with the 2024 DNC and critiquing what he sees as the party’s conformity. Willick writes that when Joe Biden was running, the majority ruled that he would be their candidate—few dared to explicitly speak up. But following his decision to drop out, Harris was swiftly and “irrevocably pronounced” his successor, quashing any uncertainty regarding a potential primary. The majority had spoken.

But is that necessarily anti-democratic? Indeed, even within this critique, it is worth considering Tocqueville’s broader reflection on democracy’s inherent contradictions. He saw the democratic process as one filled with tension—between liberty and equality, majority rule and minority rights, freedom of thought and collective conformity. Perhaps Tocqueville’s analysis suggests that democracy’s strength lies not in the absence of such tensions, but in its ability to navigate them.

The Democratic Party’s “irrevocably pronounced” decision to rally around Harris without a primary can be viewed through this lens: while it may have sacrificed some degree of deliberative openness, it is a strategic calculation to preserve party cohesion in our tumultuous political landscape. Democracy, after all, is not always about endless debate—it is also about adapting, making decisions, and moving forward.

Yes, some of our values may have been compromised. No, this isn’t the death of democracy. The DNC is just a unique reflection of some of the impurities that make democracy, democracy.